The construction subsidy (BKZ) is a one-time payment that a network operator collects from the subscriber (e.g. operator of a battery storage system) for the expansion of local, indirect network infrastructure when a new grid connection or an extension of an existing connection is required. The legal basis is the Low Voltage Connection Ordinance (NAV) at the low voltage level. At higher voltage levels, there is no immediate basis for collecting construction subsidies, but in the industry, “Position paper on the collection of construction subsidies” the Federal Network Agency (updated version dated November 2024).

In addition, there are other costs that arise for the direct, technical connection to the power grid. This includes costs for constructing the connection, e.g. for cabling or setting up control panels. Direct network connection costs are paid by the network customer independently and in addition to BKZ.

There is no uniform formula for BKZ; each network operator has its own calculation models. In practice, the calculation is according to the so-called service pricing model, which is recommended by the Federal Network Agency. The agreed connection load is multiplied by the service price of the network fee for systems of over 2,500 full usage hours per year. In the recommended model, the amount of BKZ then corresponds to the level of the service component of the network fee that a consumer with over 2,500 full hours of full use must pay per year. In practice, the amount of BKZ depends on several factors, in particular:

- Network level: Whether the connection is made to the medium-voltage, high-voltage or high-voltage network influences costs. Depending on the network area, costs may fall or rise along the voltage level; there is no clear trend here in practice.

- Connected load: The more power is required, the higher the BKZ can be.

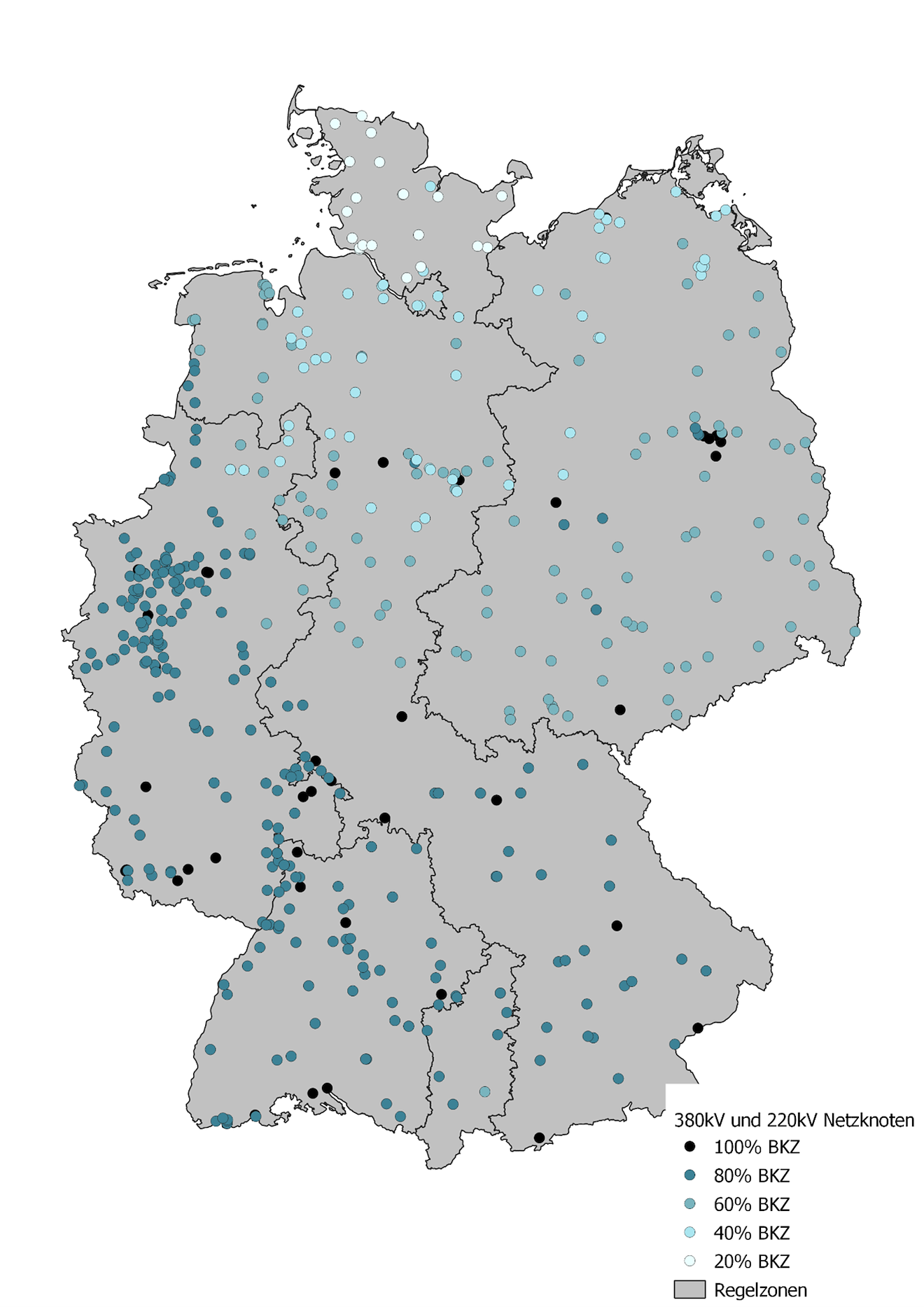

- Regional differences: In southern Germany, where the network is more load-dominated, construction subsidies are often significantly higher than in the north. In addition, fewer discounts on the BNetzA's regular calculation formula tend to be granted in the south than in the north, which further increases the north-south divide between BKZ.

Yes, and a significant one at that. The amount of the construction subsidy varies greatly from region to region and is typically significantly higher in southern Germany than in northern Germany. According to the latest position paper from the Federal Network Agency (as of November 2024), network operators are required to make the calculation bases and regional differences transparent.

For example: A battery storage system with 100 MW connection capacity in northern Germany can expect a BZ of less than €5 million — in southern Germany, however, often over €14 million. This difference of around €9 million can have a significant impact on the profitability of a project.

The map of transmission system operators across Germany shows various network nodes where it can be useful to differentiate the construction subsidy. At lighter network nodes, the construction subsidy can be reduced more than at darker network nodes.

Battery storage systems are a central component of the energy revolution. They help to temporarily store electricity from renewable sources and provide it when it is needed. This reduces the load on the grid and makes the power supply more flexible and stable.

However, a high construction subsidy can result in projects economically are no longer attractive. Although storage systems are no longer considered traditional electricity consumers by law, they still have to pay the BKZ. Many companies and associations — including Kyon Energy — are therefore calling for reform in order to no longer discriminate against storage projects.

The Federal Court of Justice (BGH) approved the collection of construction subsidies (BKZ) for battery storage systems in July 2025. The process initiated by Kyon Energy focused on the question of whether network operators for stationary battery storage systems may demand construction subsidies indiscriminately from end users, even though they relieve the electricity system and do not act like traditional end users. The consequences of the decision are far-reaching — for investment security in large battery storage systems, for the planning practice of project developers and for the framework conditions of the energy transition — and raise fundamental questions regarding the scope of action of the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA). Read more in the press release from Kyon Energy.